There are many definitions of “agent” in AI, and people argue endlessly about what qualifies. Following Anthropic’s effective context engineering for AI agents, we’ll define an agent as: LLMs autonomously using tools in a loop[1].

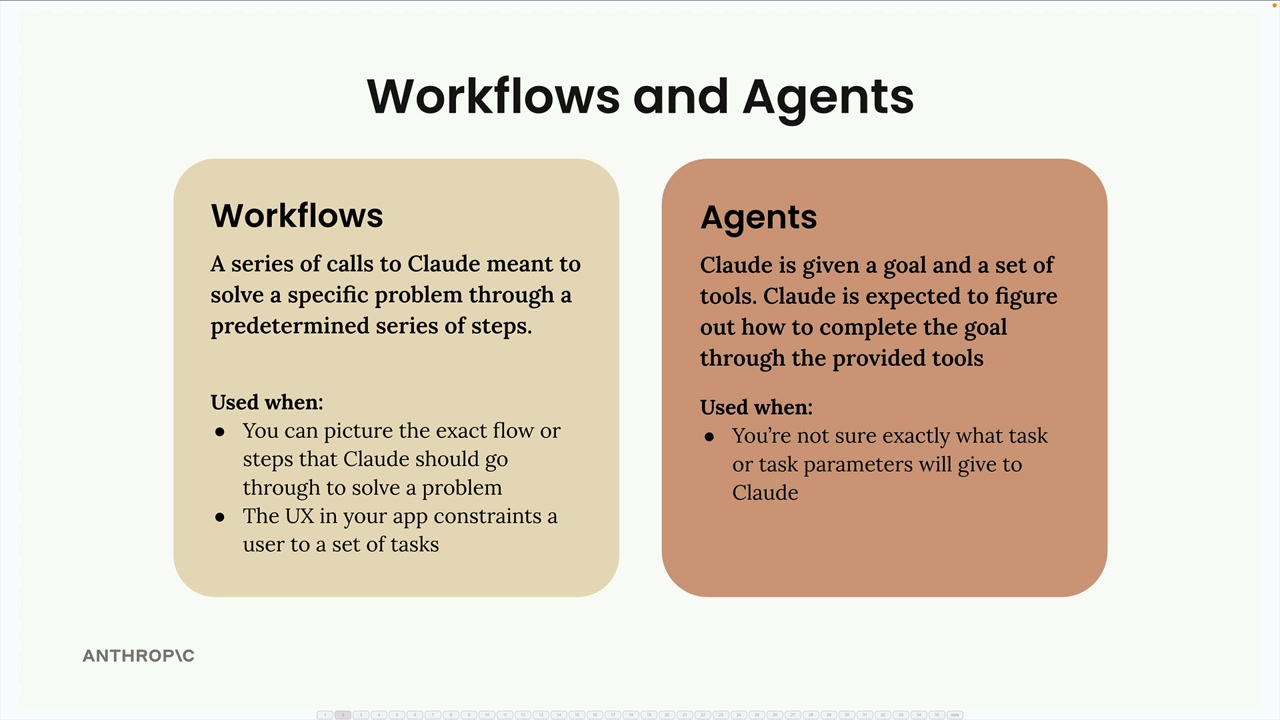

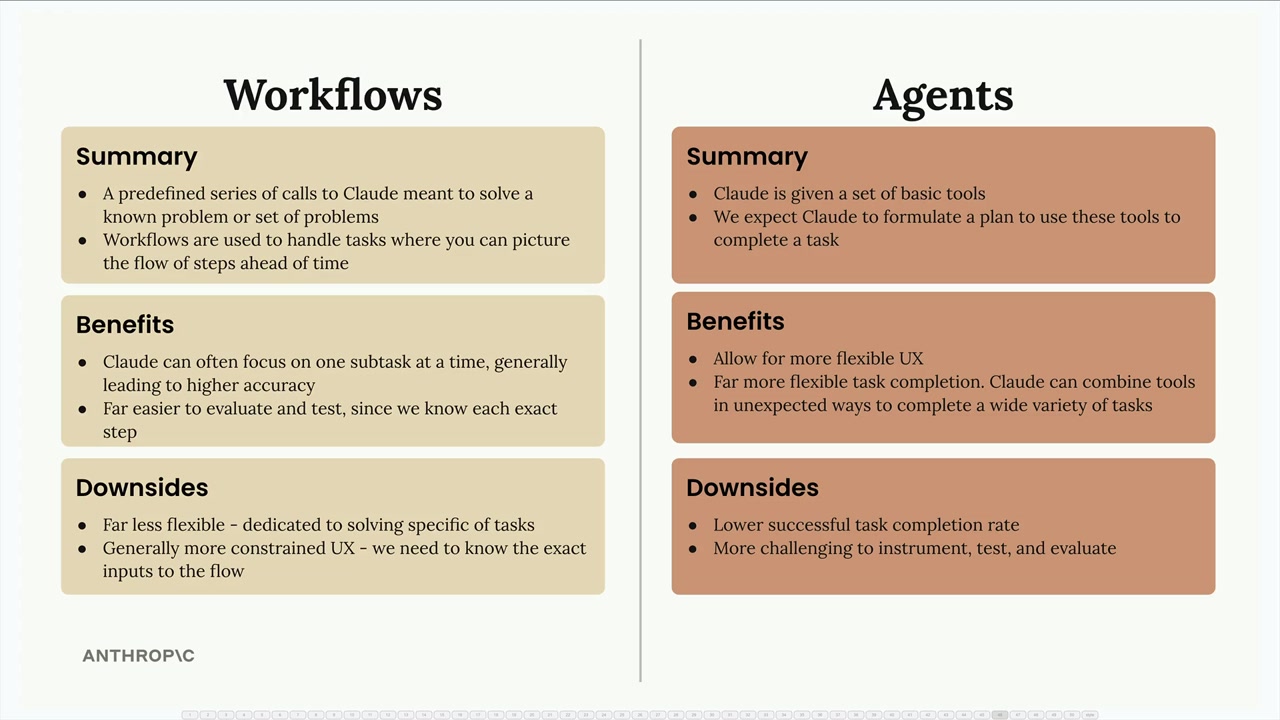

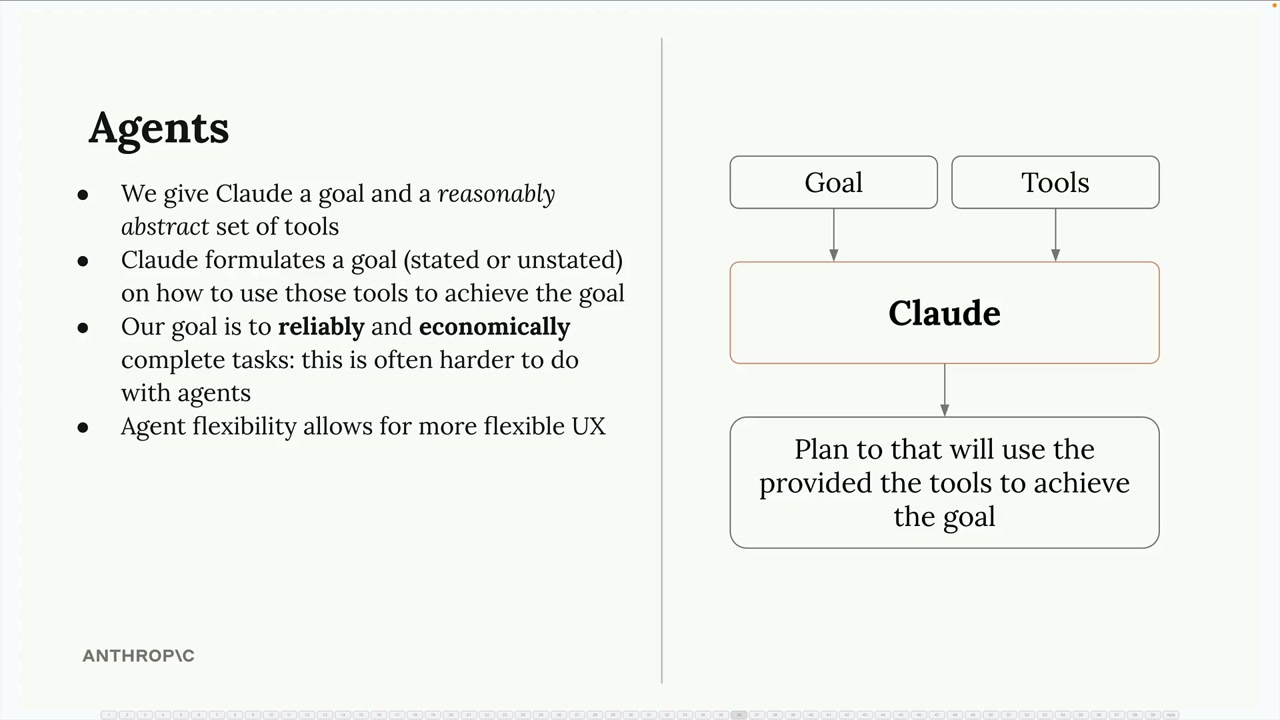

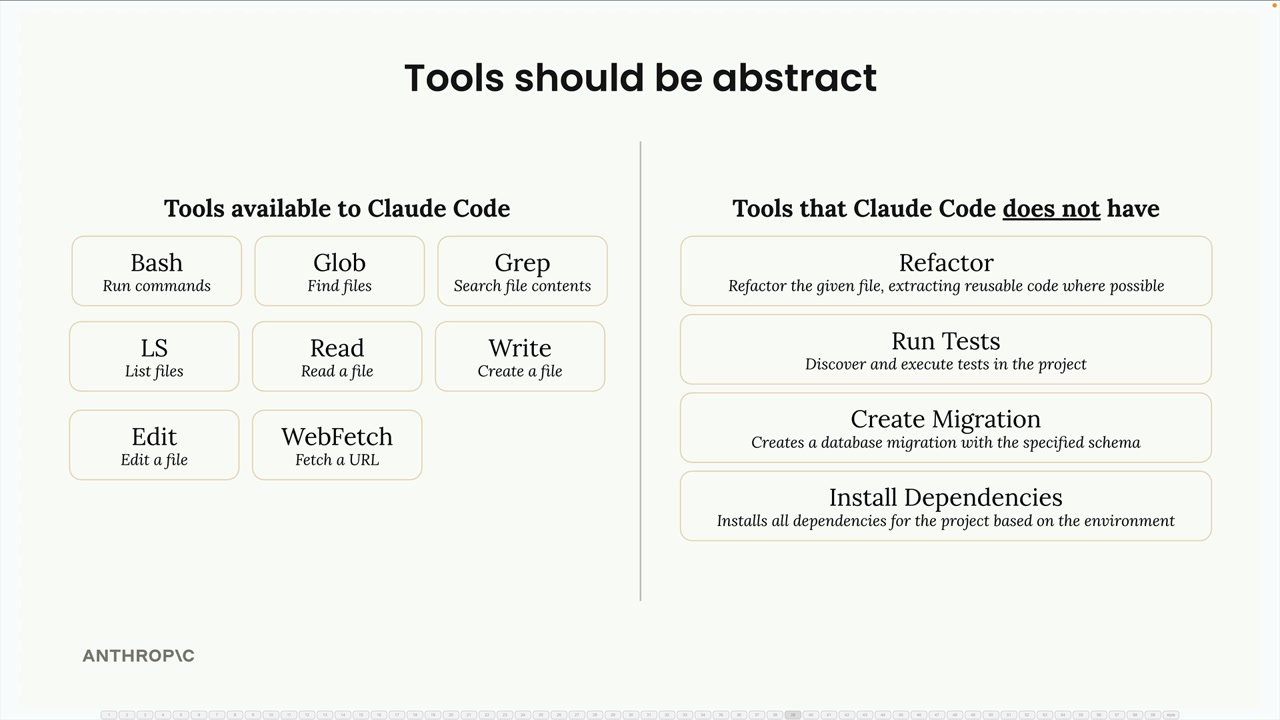

Understanding the distinction between workflows and agents—a simple heuristic that clarifies technical requirements—is essential for AI product development. Anthropic’s official Building with Claude course provides lecture slides explaining this framework:

This article focuses on agents (human-in-the-loop). The patterns you’ll learn here—tool registration, session management, approval flows, context engineering—can be simplified for workflows, but the reverse isn’t true. Workflow patterns don’t prepare you for the complexity of human collaboration.

Ready to build agents that put humans at the center?[2] Let’s explore what it really takes.†

The Single Turn Primitive

A “single turn” is one API call to the LLM and parsing its response—that’s it. Understanding this foundation is critical because while it looks simple, the reality involves thinking blocks for extended reasoning, tool use blocks for requesting actions, server-side tool executors that run those tools, and the precise message organization that combines assistant content with tool results. Get the primitive right, and complex behaviors become composition, not chaos.

How Tools Work: From Schema to Result

Now that you understand the single turn primitive, the next critical piece is understanding how tools flow through the system. When building production agents, you need to know four things:

- how to define tool schemas that Claude understands

- how Claude requests tool use

- how your server-side executor runs those tools and returns results

- and how errors become feedback that enables self-correction.

This section walks you through the complete tool lifecycle—from the JSON schema you pass to the API, to the tool_use blocks Claude generates, to the execution layer that runs your actual code, to error handling that keeps the loop resilient. Understanding this flow is essential because it reveals where intelligence lives (Claude’s adaptive tool selection and error recovery) versus where deterministic code lives (your tool executors and error formatting).

Every tool you create has three required parameters: name, description, and input_schema. But here’s what separates basic implementations from production systems: the description is where intelligence lives. This field guides Claude’s adaptive decision-making—when to use the tool, what it returns, and what constraints exist. The examples below show the critical difference between minimal definitions (what most people write) and detailed, production-ready schemas.

Three Key Parameters

Tool name identifier Claude uses to call your tool. Must match ^[a-zA-Z0-9_-]{1,64}$

Where intelligence lives. Guides Claude's adaptive decision-making. Aim for 3-4 sentences minimum—detail matters more than brevity.

JSON Schema object defining expected parameters. Tells Claude what inputs this tool needs.

JSON Schema Essentials

Essential fields for defining tool parameters. Hover over each field to learn more:

type,

properties,

required,

enum,

description,

additionalProperties,

title,

default

Check the examples below to see these fields in action

{

"name": "get_stock_price",

"description": "Gets the stock price for a ticker.",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"ticker": {

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": ["ticker"]

}

}❌ Too brief. Claude doesn't know when to use it, what it returns, or what constraints exist.

{

"name": "get_stock_price",

"description": "Retrieves the current stock price for a given ticker symbol. The ticker symbol must be a valid symbol for a publicly traded company on a major US stock exchange like NYSE or NASDAQ. The tool will return the latest trade price in USD. It should be used when the user asks about the current or most recent price of a specific stock. It will not provide any other information about the stock or company.",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"ticker": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The stock ticker symbol, e.g. AAPL for Apple Inc."

}

},

"required": ["ticker"]

}

}✓ Detailed description explains: what it does, when to use it, what it returns, and constraints.

{

"name": "get_weather",

"description": "Get the current weather in a given location. Retrieves real-time weather data including temperature, conditions, and forecast. Use this when users ask about current weather, temperature, or weather conditions for any location worldwide. Returns data in either Celsius or Fahrenheit based on the unit parameter.",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The city and state, e.g. San Francisco, CA"

},

"unit": {

"type": "string",

"enum": ["celsius", "fahrenheit"],

"description": "The unit of temperature, either 'celsius' or 'fahrenheit'"

}

},

"required": ["location"]

}

}📚 Demonstrates optional parameters and enum constraints for controlled inputs.

Claude requests tools via tool_use blocks. Your server executes them: mapping tool names to functions, validating inputs, and formatting results. This execution layer is pure engineering—error handling, timeouts, and logging all live here.

The basic pattern:

# 1. Define tool schemas (sent to Claude)

tools = [{

"name": "search_web",

"description": "Search the web for information",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {"query": {"type": "string"}},

"required": ["query"]

}

}]

# 2. Define executors (run on your server)

async def search_web_execute(tool_use):

query = tool_use["input"]["query"]

results = await search_api(query)

return f"Found: {results}"

executors = {"search_web": search_web_execute}

# 3. Execute requested tools

for block in response.content:

if block["type"] == "tool_use":

executor = executors[block["name"]]

try:

result = await executor(block)

tool_result = {

"type": "tool_result",

"tool_use_id": block["id"],

"content": result

}

except Exception as e:

tool_result = {

"type": "tool_result",

"tool_use_id": block["id"],

"content": f"Error: {e}",

"is_error": True

}The manual loop above works, but production systems use an abstraction that handles errors, timeouts, and logging automatically. The execute_tools() function encapsulates this pattern:

async def execute_tools(

content_blocks: list, # Response content from run_agent_turn

tool_executors: dict, # {"tool_name": executor_function}

default_timeout: float = 20.0,

tool_timeouts: dict | None = None, # Per-tool timeout overrides

verbose: bool = False

) -> list[dict]:

"""

Execute all tool_use blocks and return tool_result blocks.

Handles:

- Extracting tool_use blocks from response content

- Running each executor with timeout protection

- Error handling (timeouts, exceptions, missing executors)

- Formatting results as tool_result blocks

"""Usage example:

from tool_executor import execute_tools

# After getting response from Claude

tool_results = await execute_tools(

content_blocks=response.content,

tool_executors=EXECUTORS,

default_timeout=20.0,

tool_timeouts={

"synthesize_audio": 120.0, # Slow tools get more time

"search_web": 10.0 # Fast tools get less

},

verbose=True

)

# Send results back to Claude

if tool_results:

messages.append({"role": "assistant", "content": response.content})

messages.append({"role": "user", "content": tool_results})Errors aren’t failures—they’re feedback mechanisms that enable self-correction. Tools return explicit error dicts, and execute_tools() converts them to the is_error flag that Claude uses to adapt its strategy.

# Tools return dicts for explicit error signaling

async def search_execute(tool_use):

query = tool_use["input"]["query"]

if not query.strip():

return {"success": False, "error": "Query cannot be empty"}

try:

results = await search_api(query)

return {"success": True, "content": format_results(results)}

except Exception as e:

return {"success": False, "error": f"Search failed: {e}"}

# execute_tools() converts error dicts to is_error flag

result = await executor(tool_use)

if isinstance(result, dict) and not result.get("success", True):

tool_results.append({

"type": "tool_result",

"content": result["error"],

"is_error": True # Signals to Claude this is an error

})Real example of self-correction (Claude Code’s actual behavior):

Turn 1:

User: "Read the extended thinking docs"

Agent: [calls read tool]

Turn 2:

Error: "File content (30043 tokens) exceeds limit (25000).

Use offset and limit parameters to read in portions."

Turn 3:

Agent: [adapts] "I'll read it in chunks"

[calls read with offset=0, limit=200]

[continues until complete]Errors don’t break the loop—they enable intelligence.

As your system grows, keep schemas and executors together. Here’s the recommended file structure:

project/

├── tools/

│ ├── __init__.py # Auto-collects all tools

│ ├── search.py # Search: schema + executor

│ └── weather.py # Weather: schema + executor

└── main.py # Your agent codeEach tool file contains both schema and executor:

# tools/search.py

from anthropic.types import ToolParam

TOOL_SCHEMA = ToolParam({

"name": "search_web",

"description": "Search the web for information",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {"query": {"type": "string"}},

"required": ["query"]

}

})

async def search_execute(tool_use):

query = tool_use["input"]["query"]

if not query.strip():

return {"success": False, "error": "Query cannot be empty"}

results = await search_api(query)

return {"success": True, "content": f"Found: {results}"}Auto-collect in tools/__init__.py:

from .search import TOOL_SCHEMA as search_schema, search_execute

from .weather import TOOL_SCHEMA as weather_schema, weather_execute

TOOLS = [search_schema, weather_schema]

EXECUTORS = {"search_web": search_execute, "weather": weather_execute}Then use in your main code:

from tools import TOOLS, EXECUTORS

response = await client.messages.create(messages=messages, tools=TOOLS)This organization scales to hundreds of tools without scattered code or if/elif chains.

Tool design is arguably the most important part of building production agents—the quality of your tools directly determines what your agent can accomplish. Beyond data fetching, tools can be creative instruments for reasoning and interaction. The think tool, for instance, doesn’t fetch data at all—it gives Claude space to pause mid-sequence and reason about tool results before deciding next steps, enabling sophisticated sequential decision-making (following the chain-of-thought pattern).

Similarly, you might design a clarify_question tool that prompts users when their intent is ambiguous, or a propose_options tool that presents multiple choices (“Did you mean option A, B, or C?”) with descriptions and lets users select. These interactive tools transform agents from simple request-response systems into collaborative problem solvers that guide users through complex workflows. The schema you write, the errors you craft, and the creativity you bring to tool design—these are what separate basic implementations from production-grade systems.

The Multi-Turn Loop: Autonomy Through Iteration

The loop is what transforms a single API call into an autonomous agent. It repeatedly invokes Claude, executes tools, and builds conversation history until the task completes naturally. Four critical aspects define production loops: loop control (preventing infinite execution), message management (building the history correctly), context engineering (avoiding token overflow), and user interaction (display vs. blocking tools).

The loop continues until Claude’s stop_reason is "end_turn" instead of "tool_use". A max_steps limit prevents infinite loops (set to 10-20 for most tasks). The loop yields progress events to the frontend, enabling real-time UI updates showing which tools are being used. When max steps is reached, Claude receives feedback and makes one final call to gracefully summarize.

async def run_agent_loop(messages, max_steps=15):

"""Agent loop that yields progress events for frontend"""

step = 0

while True:

step += 1

# Check if max steps reached

if step > max_steps:

messages.append({

"role": "user",

"content": f"You have used {max_steps} steps. Please summarize what you've accomplished."

})

final_response = await client.messages.create(messages=messages, max_tokens=4096)

yield {"type": "complete", "response": final_response}

return

# Call Claude

response = await client.messages.create(

messages=messages,

tools=TOOLS,

max_tokens=4096

)

# Extract content for progress events

tool_calls = [b for b in response.content if b.get("type") == "tool_use"]

text_blocks = [b.get("text") for b in response.content if b.get("type") == "text"]

# Yield assistant message to frontend

if text_blocks:

yield {"type": "assistant_message", "content": " ".join(text_blocks)}

# Yield tool execution events (for non-display/interactive tools)

if tool_calls:

tool_names = [tc["name"] for tc in tool_calls]

yield {"type": "tools_executing", "tools": tool_names}

messages.append({"role": "assistant", "content": response.content})

# Check stop condition

if response.stop_reason != "tool_use":

yield {"type": "complete", "response": response}

return

# Execute tools

tool_results = await execute_tools(response.content, EXECUTORS)

# Check for interactive tools (pause loop)

if any(r.get("requires_user_input") for r in tool_results):

yield {"type": "awaiting_user_input"}

return # Stop here - resume when user responds

messages.append({"role": "user", "content": tool_results})The generator pattern enables streaming responses to the frontend via Server-Sent Events (SSE) or WebSocket. This architecture—including how to handle streaming, state persistence, and interactive tool pause/resume—will be covered in detail in the FastAPI architecture article.

The messages list grows with each iteration. Assistant messages contain the full response.content (text blocks, tool_use blocks, thinking blocks). Tool results are always user role, formatted as tool_result blocks. This alternating pattern builds the conversation history that Claude uses for context in subsequent turns.

# Initial state

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Debug authentication errors in the system"}

]

# After Turn 1: Claude requests grep tool

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Debug authentication errors..."},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": [

{"type": "text", "text": "I'll search for authentication errors."},

{"type": "tool_use", "id": "toolu_1", "name": "grep", "input": {...}}

]

}

]

# After Turn 2: Tool results returned

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Debug authentication errors..."},

{"role": "assistant", "content": [...]},

{

"role": "user",

"content": [

{"type": "tool_result", "tool_use_id": "toolu_1", "content": "Found 50 errors..."}

]

}

]

# After Turn 3: Claude analyzes and requests read tool

messages = [

# ... previous messages ...

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": [

{"type": "text", "text": "I found 50 errors. Let me read the auth handler."},

{"type": "tool_use", "id": "toolu_2", "name": "read", "input": {...}}

]

}

]

# Pattern continues until stop_reason != "tool_use"After 10 loop iterations, you might have 20+ messages consuming 100K+ tokens. Tool results are the main culprit—a single grep can return 50KB of matches. Three strategies prevent overflow: truncate tool results to reasonable sizes, limit max loop steps as a hard stop, and implement message pruning for very long conversations (keep first N system messages + last M messages, drop middle).

# Strategy 1: Tool result truncation (in tool_executor.py)

MAX_TOOL_RESULT_SIZE = 30000 # Characters

if len(result) > MAX_TOOL_RESULT_SIZE:

result = result[:MAX_TOOL_RESULT_SIZE]

result += f"\n\n[Output truncated from {original_size} to {MAX_TOOL_RESULT_SIZE} chars]"

# Strategy 2: Max steps limit (prevents infinite loops)

max_steps = 15 # Typical: 10-20

for step in range(max_steps):

# ... loop logic

# Strategy 3: Message pruning (advanced - for very long conversations)

if len(messages) > 30:

# Keep first 5 (system context) + last 20 (recent context)

messages = messages[:5] + messages[-20:]This section focuses on token-wise context engineering—preventing overflow through truncation and limits. More sophisticated approaches exist: dynamically injecting context when needed, selectively removing messages based on relevance, or restructuring conversation history for specific tasks. These advanced techniques for intelligent context manipulation will be covered in future articles on production API architectures.

Display tools render UI elements without blocking the loop. They send data to the frontend for visualization, then immediately return a simple confirmation. Examples: grammar analysis reports, progress indicators, data tables, charts. The tool result just confirms the display happened—the actual content lives in the frontend render.

# Example: Grammar analysis display tool

async def analyze_writing_execute(tool_use):

text = tool_use["input"]["text"]

# Perform analysis

analysis = {

"errors": [...],

"suggestions": [...],

"readability_score": 85

}

# Send to frontend for display (WebSocket, SSE, or response metadata)

await send_to_frontend({

"type": "grammar_report",

"data": analysis # Frontend renders nice report UI

})

# Tool result is minimal - just confirmation

return {

"success": True,

"content": "Grammar analysis report has been displayed to the user."

}

# Loop continues immediately - no waitingKey distinction: One-way communication from agent to frontend. Other examples include show_progress, display_chart, and render_table—all push data for display without waiting for user response.

Interactive tools pause the loop and wait for user input. When Claude calls propose_options or clarify_question, the tool sends choices to the frontend, the current request ends, and execution resumes when the user responds in a new request. This requires special API architecture to persist conversation state and resume from the exact point where the loop paused.

# Example: Propose options and wait for user choice

async def propose_options_execute(tool_use):

question = tool_use["input"]["question"]

options = tool_use["input"]["options"] # ["Option A", "Option B", "Option C"]

# Send to frontend

await send_to_frontend({

"type": "multiple_choice",

"question": question,

"options": options

})

# ⚠️ IMPORTANT: This requires special API architecture

# The current request ends here and returns to the frontend.

# The user's selection comes back in a NEW request.

# The loop must resume from this exact point.

#

# Implementation requires:

# - Saving conversation state (messages + loop position)

# - Returning partial response to frontend

# - Resuming loop when user responds

#

# This pattern will be covered in detail in the FastAPI architecture article.

return {

"success": True,

"content": "Waiting for user to select an option...",

"requires_user_input": True # Signal to pause loop

}

# When user responds, their selection becomes the tool result:

# {"type": "tool_result", "tool_use_id": "...", "content": "User selected: Option B"}

# Loop resumes from this point.Key distinction: Two-way blocking communication. Agent asks, waits for user response, then continues. Examples include clarify_question, confirm_action, and request_approval—all require pausing execution until the user responds.

Managing Conversation State

Production agents need a MessageManager abstraction that handles persistence, caching, and context engineering—keeping the loop code clean and focused on agent logic.

The complete implementation—including Redis/PostgreSQL integration, token budget queries, and interactive tool state management—will be covered in detail in the FastAPI architecture article.

Building Production Agents: What We’ve Covered

This guide walked through the complete architecture of production agents, from the single-turn primitive (the atomic unit of agent interaction) to the multi-turn loop that enables autonomy. We explored how tool design goes beyond simple data fetching—errors become feedback mechanisms that enable self-correction, the think tool chains reasoning through tool calls, and interactive tools create collaborative workflows.

The multi-turn loop emerged as a sophisticated system: generator patterns for frontend progress, max steps with graceful feedback, context engineering to prevent token overflow, and the distinction between display tools (one-way presentation) and interactive tools (blocking for user input). Finally, we introduced message management—the abstraction that handles L1/L2 caching, token budget loading, and loop state persistence. These aren’t theoretical patterns; they’re production requirements discovered through real user traffic and scaled systems.

The next article, “Building Production Agent APIs with FastAPI”, moves from concepts to implementation. We’ll build the complete MessageManager class (Redis + PostgreSQL integration), implement session management with state persistence, create streaming response handlers (SSE and WebSocket patterns), show how interactive tools pause and resume across requests, and design the frontend integration layer. Step-by-step, we’ll transform these architectural patterns into working production code that scales.

References

[1] Anthropic. (2025). Effective Context Engineering for AI Agents. Retrieved from https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/effective-context-engineering-for-ai-agents

[2] Throughout this guide, we’ll use Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4.5 for demonstrations. Claude consistently outperforms other models in agentic reasoning tasks, as validated by independent evaluation. See: Patwardhan et al. (2025). GDPval: Evaluating AI Model Performance on Real-World Economically Valuable Tasks. arXiv:2510.04374. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.04374 | Blog: https://openai.com/index/gdpval/